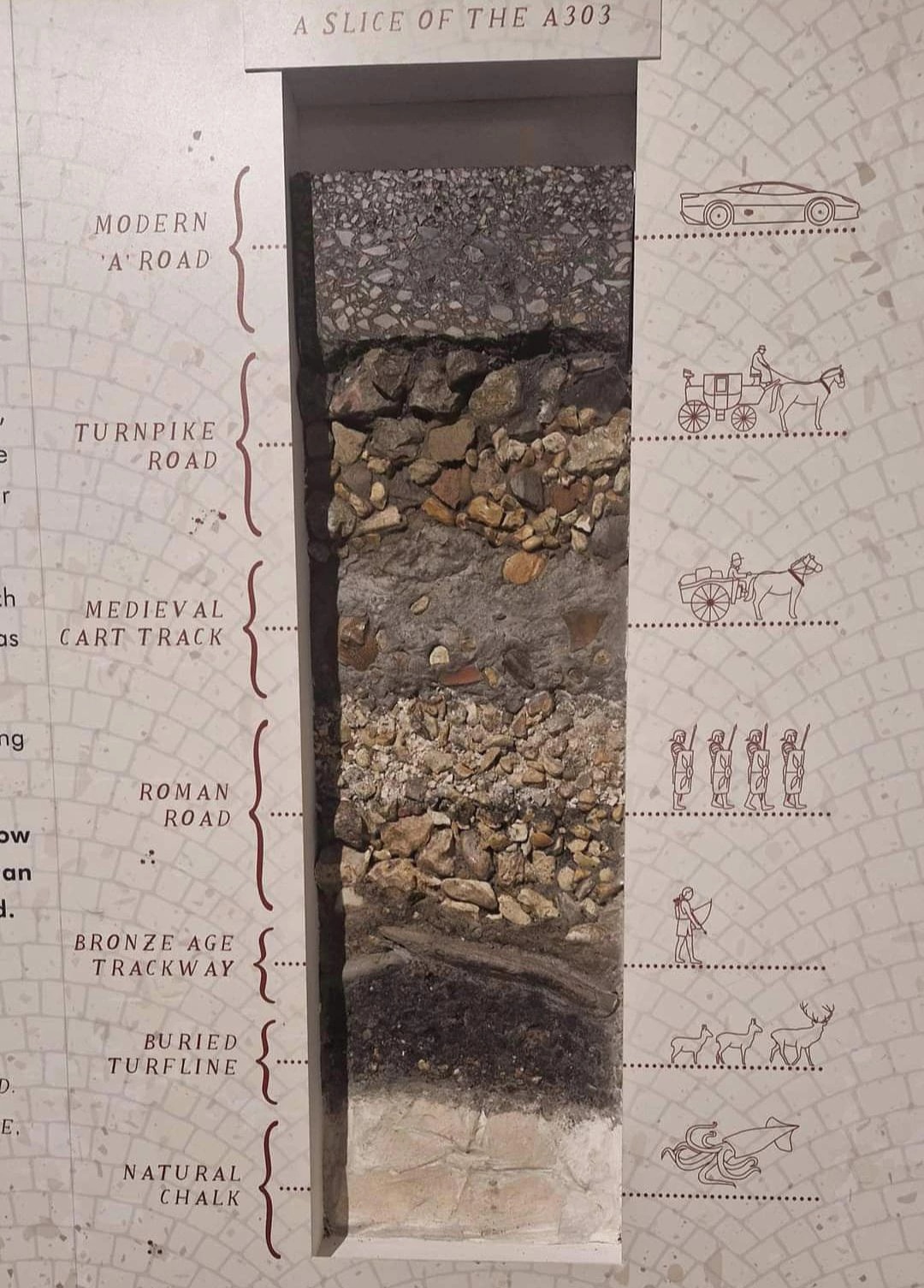

An image that recently surfaced on social media shows a slice of England’s iconic A303 road with the different layers built over millennia. Here’s the history behind those layers and what the future of the road looks like.

A slice from the iconic A303 road in England clearly showing the different layers built over millennia. Source

The A303 is a major road that connects London to the South West of England, passing through some of the most scenic and historic landscapes in the country. One of the most iconic sections of the A303 is the one that runs near Stonehenge, the ancient monument that dates back to 5,000 years ago.

But how did this road evolve from natural chalk to modern asphalt? And what are the challenges and opportunities of upgrading it to improve connectivity and preserve heritage?

The origins of the A303 can be traced back to prehistoric times, when people used natural features such as chalk ridges and river valleys to travel across the land. The area around Stonehenge was a focal point for ancient rituals and ceremonies, attracting people from far and wide.

Some of the earliest tracks that crossed this landscape were later incorporated into Roman roads, such as the Fosse Way and the Portway, which linked important settlements and military sites.

Cross-section of a Roman road. Source

After the Roman withdrawal, the roads fell into disrepair and were largely abandoned until the medieval period, when new routes emerged to serve pilgrims, traders and travellers. The A303 follows parts of these old roads, such as the Harrow Way and the Herepath, which were often marked by milestones, crosses and inns.

The road also passes by several historic landmarks, such as Old Sarum, Salisbury Cathedral, Wardour Castle and Montacute House.

The road network expanded and improved during the Georgian and Victorian eras, as new modes of transport such as coaches, railways and bicycles became popular. The A303 was part of a coaching route between London and Exeter, which was frequented by famous writers such as Jane Austen, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth.

The road also witnessed some of the first experiments with steam-powered vehicles, such as Richard Trevithick’s Puffing Devil in 1801.

The advent of motor cars in the 20th century led to a surge in traffic and demand for better roads. The A303 was designated as a trunk road in 1933, linking the M3 in Hampshire and the M5 in Somerset. The road was gradually upgraded to dual carriageway in some sections, but remained single carriageway in others, creating bottlenecks and congestion.

One of the most notorious sections was the one near Stonehenge, where traffic had to slow down or stop to pass through a narrow gap between the stones and a nearby hill.

The A303 near Stonehenge c.1930. Sign reads “Fork left for Exeter”. The houses and AA phone box have since been demolished. The road to the right was the A344. Image credit: Unknown

The A303 has been the subject of several proposals for improvement since the 1980s, but none of them have been implemented due to environmental, archaeological and financial constraints.

The road runs within 165 metres of Stonehenge, which is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site that covers a large area of archaeological significance. Any changes to the road would have to balance the needs of transport, tourism, heritage and ecology.

The A303 road passing by Stonehenge. Image credit: Pam Brophy

The latest plan for upgrading the A303 is to build a 3.3 km tunnel under Stonehenge, which would remove the sight and sound of traffic from the monument and restore its setting within the landscape.

The tunnel would be part of a wider scheme to transform the A303 into an expressway to the South West, with dual carriageway sections between Amesbury and Berwick Down, Sparkford and Ilchester, and Taunton and Southfields. The scheme aims to improve journey times, reliability, safety and resilience for road users, as well as enhance access to cultural and natural attractions along the route.

Stonehenge as seen from the A303 in 2009. The A303, in the foreground, is planned to be modified. The A344, which passed close to Stonehenge, was removed in 2013, leaving just a short access road from Airman’s Corner. Image credit: Peter Trimming

Old A344 at Stonehenge, closed in 2013 and grassed over (December 2013). Image credit: Ashley Columbus

The tunnel project has been supported by some organisations such as Historic England and the National Trust, but opposed by others such as UNESCO and some archaeologists, who argue that it would cause irreversible damage to the World Heritage Site and its hidden treasures.

The project is currently undergoing public consultation and environmental assessment, with a final decision expected in 2022. If approved, construction could start in 2023 and finish by 2028.

The A303 is more than just a road – it is a layer cake of history that reflects how people have travelled across this land for millennia. From natural chalk to modern road, it has witnessed many changes and challenges over time. The future of the A303 will depend on how we balance our needs for connectivity and preservation in this unique and precious landscape.

Sources: 1, 2, 3

Written by Tamás Varga

A sociologist and English major by degree, I’ve worked in the area of civil society & human rights and have been blogging in the fields of travel, nature & science for over 20 years.