The megalodon was one of the most ferocious predators to have ever lived on Earth, having ruled the seas 23 million years ago.

But despite being 52ft long and weighing a whopping 61 tonnes, it is known only from fragmentary remains, such as its teeth.

What is even more interesting is what came before megalodon and evolved into the beast of the deep.

Now, scientists in Australia have gained some more insight after uncovering a tooth that belonged to the 40ft-long ancestor and closest relative to megalodon.

Shark graveyard: The megalodon was one of the most ferocious predators to have ever lived on Earth, having ruled the seas 23 million years ago. Now, scientists in Australia have uncovered a tooth that belonged to the 40ft-long ancestor and closest relative to megalodon

Despite being 52ft long and weighing a whopping 61 tonnes, megalodon is known only from fragmentary remains, such as its teeth

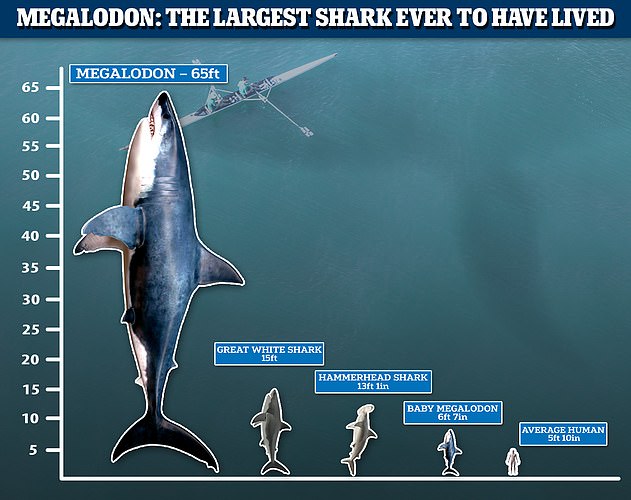

THE LARGEST SHARK THAT EVER LIVED

O. megalodon was not only the biggest shark in the world, but one of the largest fish ever to exist.

Estimates suggest it grew to between 49 feet and 59 feet (15 and 18 metres) in length, three times longer than the largest recorded great white shark.

Without a complete megalodon skeleton, these figures are based on the size of the animal’s teeth, which can reach 7 inches long.

Most reconstructions show megalodon looking like an enormous great white shark, but this is now believed to be incorrect.

It was found along with more than 750 other fossilised teeth in a shark graveyard at the bottom of the Indian Ocean.

‘The teeth look to come from modern sharks, such as mako and white sharks, but also from ancient sharks including the immediate ancestor of the giant megalodon shark,’ said Dr Glenn Moore, curator of Fishes at the Western Australian Museum.

‘This shark evolved into the megalodon, which was the largest of all sharks but died out about 3.5 million years ago.’

Dr Moore, who was part of the team who made the discovery, said it was astounding that such a large number of teeth were collected from a relatively small area on the seafloor.

‘We’ve also found a few mako and white shark teeth during the under way voyage but nothing like the numbers found during the previous voyage,’ he added.

‘It’s incredible to think we’ve collected all these teeth in a net from the seafloor some 4 to 5 km below the ocean surface.’

Scientists, led by the Museums Victoria Research Institute, made the surprising discovery of the shark graveyard during the final trawl of a voyage at a depth of 18,000ft (5,400 metres).

This voyage was one of two biodiversity survey’s of Australia’s newest marine parks and was carried out by experts on the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) research vessel.

As well as a shark graveyard, they also discovered the specimen of a new species of shark.

‘Early in the voyage, we collected a striking small, stripey hornshark,’ said shark expert Dr Will White, from CSIRO’s Australian National Fish Collection.

‘This species is unique to Australia, but it hasn’t yet been described and named.

‘The specimen we collected will be incredibly important to science because we’ll use it to describe the species.’

Dr Moore, who was part of the team who made the discovery, said it was astounding that such a large number of teeth were collected from a relatively small area on the seafloor

Scientists, led by the Museums Victoria Research Institute, made the surprising discovery of the shark graveyard during the final trawl of a voyage at a depth of 18,000ft (5,400 metres)

Scientists found more than 750 fossilised teeth in a shark graveyard at the bottom of the Indian Ocean

Previous studies suggest the megalodon reached lengths of at least 50ft (15 metres) and possibly as much as 65ft (20 metres)

Hornsharks include the well-known Port Jackson shark and are generally slow-moving species found in shallow waters.

They spend most of the day camouflaged among rocks and seaweed on the seafloor and come out at night to feed.

However, this new species lives in water over 490ft (150 metres) deep and scientists know next to nothing about its behaviour.

Dr White said biodiversity surveys are always exciting because experts never know what they are going to find.

‘Australia has a truly enormous marine estate that’s home to some of the most diverse marine life on the planet but we still know very little about what lives beneath the waves,’ he added.

‘From the very first survey on this voyage, we’ve been making new discoveries and collecting data that will be vital in helping to protect and conserve the life in our oceans.’

Scientists have used a range of equipment to study marine life and seabed habitats in the Indian Ocean, including underwater towed and remote cameras.

Several shark species have been captured on film during the voyage.

Dr John Keesing, from CSIRO, said the discovery of a new species was quite common on biodiversity surveys such as this one.

‘It’s been estimated that around a third of the species collected on recent biodiversity survey voyages on RV Investigator may be new to science,’ he added.

The voyage was one of two biodiversity survey’s of Australia’s newest marine parks and was carried out by experts on the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) research vessel

‘The discoveries we make aren’t just limited to new species. These voyages give us the opportunity to learn more about marine ecosystems, as well as species range, abundance and behaviour.’

The discoveries emphasise the importance of marine biodiversity survey voyages and the significant contribution they make to better understanding the life in our oceans.

‘From small, new, bottom-dwelling sharks, to massive ancient mega-sharks that once roamed the oceans, these biodiversity surveys give us vital insights into the life in our oceans,’ Dr Keesing said.

Parks Australia’s Jason Mundy said the discoveries will help to manage the remote marine parks, now and into the future.

‘It shows there is more to learn about our 60 Australian Marine Parks, especially those in deep and difficult to access environments,’ he added.

‘This is made possible through partnerships with research organisations and universities.’