Mankind has used animals such as onagers (wild donkeys), horses, camels, elephants, and dogs in conflicts for thousands of years, but no other animal has been employed so widely and continuously and was at times so comprehensively protected as the horse. Although its history and development generally paralleled that of armor for man —both employing the same materials (metal, leather, and textile) and decorative techniques—horse armor was generally rarer, being reserved mainly for the elite heavy cavalry and predominantly for battle.

Antiquity

What is probably the first man-made armor for any animal appeared as early as 2600–2500 B.C. in the Mesopotamian city of Ur , where onagers, used for pulling battle carts, seem to have been protected with chest defenses. During the following 2,000 years, horse armor evolved in the Near East and Egypt from protective coverings for chariot horses. By the ninth century B.C., horsemanship and the development of mounted warfare had spread to the East, West, and North.

The earliest evidence for European horse armor dates to the eighth and seventh centuries B.C., when it appeared in Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, doubtlessly introduced from the East. The Greeks knew horse armor from their Persian enemies (who had inherited it from the Assyrians), but its use seems to have been rare, except for the Western provinces of southern Italy and Sicily, where head defenses (shaffrons) and breastplates (peytrals) are verifiable as early as the fourth century B.C.

The Romans largely neglected the use of cavalry in favor of foot soldiers, but protective horse equipment was occasionally seen during the late Republic . Initially used for ceremonial training practices, the first units of armored cavalry proper were introduced under Emperor Hadrian . Specialized subunits of heavily armored cavalry, known as clibanarii and modeled on Rome’s Parthian and Sassanian enemies, were probably introduced during the third and early fourth centuries A.D. Their regular employment throughout other provinces, including those in western Europe, may have ensured that the use of horse armor survived well into the fifth century. With the decline of Roman rule, however, the use of protective horse equipment north of the Alps appears to have ceased altogether.

The Medieval Period

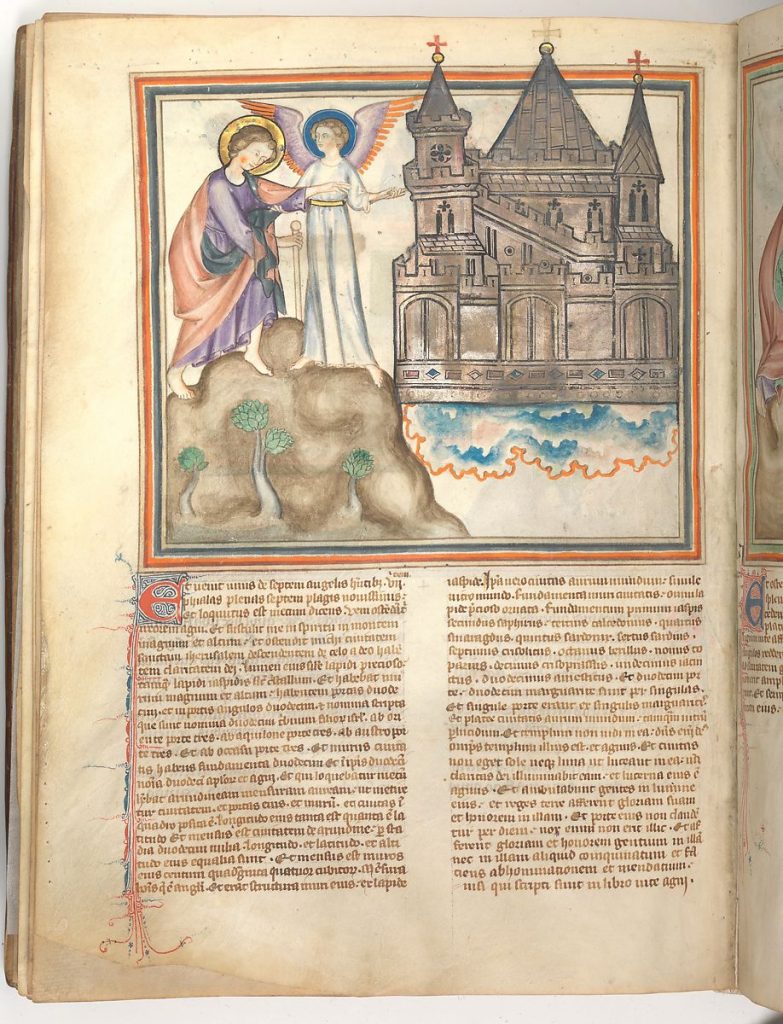

It was not until the twelfth century that horse armor was gradually reintroduced in western Europe. Like the contemporaneous mounted warrior , the horse was clad in mail armor and, presumably, wore padded and quilted garments underneath for comfort and additional protection. Caparisons, large textile coverings for the entire horse, also appeared during the late twelfth century.

When thickly padded and quilted, caparisons could assume protective qualities as well, but the majority appear to have been intended to bear heraldic colors or the rider’s coat of arms. By the first quarter of the thirteenth century, both mail trappers and caparisons were in use throughout Europe.

Early plate defenses, including shaffrons, began to make their appearance in medieval Europe after about 1250. Shaffrons were presumably made of shaped and hardened leather (cuir bouilli), or perhaps even metal, and were employed both on the battlefield and in tournaments. Frequently adorned with crests matching those on the helmets of their riders, they could be worn over or beneath the caparison or together with a mail trapper. After 1300, inventories list a variety of different horse armor elements, including trappers of mail, thickly padded and quilted trappers or caparisons, and plate defenses for the sides and rear of the horse. In its general construction and appearance, such equipment does not appear to change dramatically until the middle of the fourteenth century, and the entire range could be used in various combinations.

A small ivory chess piece illustrates the fullest protection available for horses after the middle of the fourteenth century.

The Renaissance and Early Modern Period

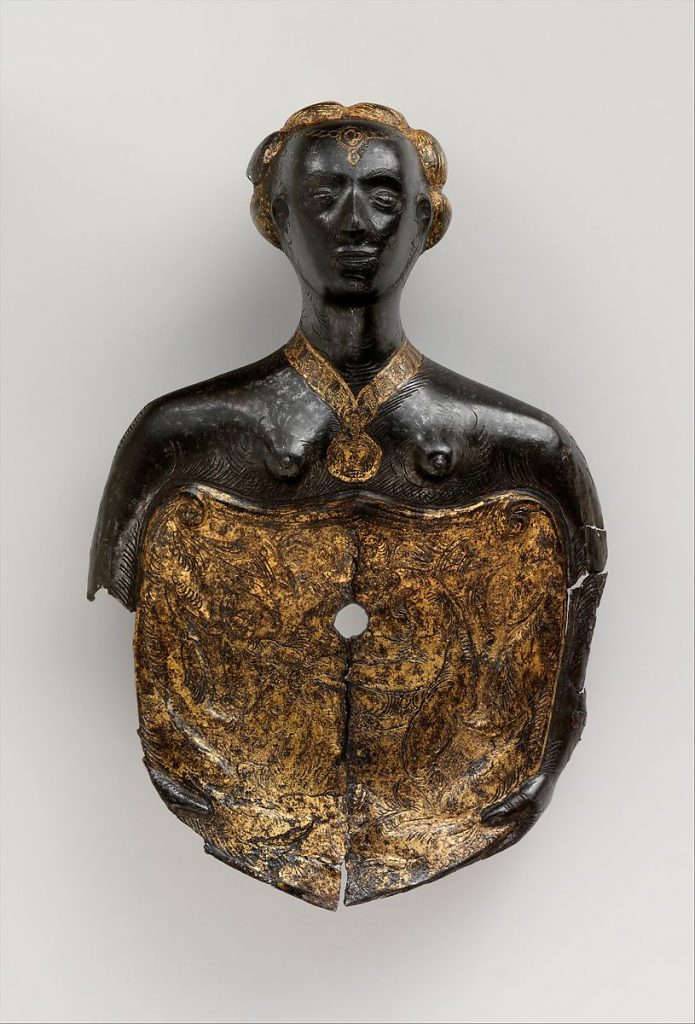

The early fifteenth century witnessed the final completion of plate armor for both man and horse, while the use of mail trappers declined. By the mid-fifteenth century, metal plates and leather were the dominant materials for all elements of horse armor, and a “full bard” now comprised a shaffron, closed neck defense (crinet), chest defense (peytral), panels for the sides (flanchards), and a rump defense (crupper). Caparisons disappeared from the battlefields but remained a decorative feature for tournaments and other ceremonial occasions until the late sixteenth century. From the early fifteenth century onward, the front and rear of saddles for war and tournament were covered with steel plates; these armored saddles completed a system of plate defenses that provided continuous protection from the top of the rider’s head to below the horse’s rump.

By the end of the century, individual workshops, like that of the celebrated Augsburg armorer Lorenz Helmschmid (ca. 1445–1516), made matching sets of armor for horse and rider, including saddles. The Helmschmid workshop also produced spectacular bards that all but completely enclosed the horse’s body, including the underside of the girth and abdomen, as well as the legs. Complete to the extreme, and of such technical complexity and considerable expense that they were most likely intended solely for ceremonial purposes and as diplomatic gifts.

Plate armor offered a variety of possibilities for decoration that extended beyond the use of textile, painted leather, or the rare gilt fringes of mail trappers. Edges could be scalloped and pierced with various patterns, and surfaces were embossed with ridges and grooves, reflecting northern Gothic taste .

Appliqués of copper alloy as well as bluing, gilding, and etching were in use by the last quarter of the century. In rare instances, the surfaces were embossed with figural decoration.

The late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries also saw the development of armor specially designed for horses used in tournaments. A distinctive type of shaffron, with a prominent medial ridge or even a comb, appears to have usually been made from leather. Since the early fifteenth century, horses occasionally had their eyes covered for specific types of the joust (in order to prevent them from shying during a charge), which led to the invention—during the second half of the fifteenth century—of the so-called blind shaffron, which was primarily employed in the German lands.

Bards for field use were undoubtedly employed for tournaments, particularly in the tourney, or melée (a mock combat fought by groups of contestants), but in the joust (as well as sometimes in the tourney) they were usually replaced by a form of large crescent-shaped cushion, called a buffer or hourt, worn across the breast of the horse like a peytral. These defenses remained a standard element well into the sixteenth century), until the gradual adoption of the separating barrier, or “tilt,” which rendered defenses for the horse’s body unnecessary.

A number of complete bards and a much greater number of detached elements of horse armor are preserved from the sixteenth century. Numerous pictorial sources demonstrate the wide variety of equipment in use during these decades: full, light, and blind shaffrons; full crinets constructed from a mix of plate and mail; and and even crinets solely of mail exist side by side, while cruppers either cover the horse’s entire hind quarters or merely consist of two large side panels.

Documentary sources also reveal the prevalence of bards made from hardened leather, which, in contemporaneous art, are readily identifiable by the laces connecting the panels. Comparatively inexpensive, lighter in weight, and offering endless possibilities for painting and other embellishment, leather bards were undoubtedly far more commonplace than their survival state would suggest.

Horse armor enjoyed its final flowering during the first half of the sixteenth century, and full bards remained common until about 1550, as long as the heavy cavalry was still armed with the traditional lance.

Every element, from the small shields (escutcheon) on shaffrons down to the saddle steels, continued to be decorated in a variety of different techniques. During the second half of the century, though full bards were still being made (now mainly for display and occasional tournament use), lighter defenses such as steel-reinforced leather strapwork began to appear.

In many instances, both field and tournament armors comprised no more than matching shaffrons and saddles. Shaffrons changed along similar lines, and, particularly in Germany, lighter versions were increasingly more prevalent.

As before, the decoration of sixteenth-century horse armor reflects that of the man’s armor. After about 1525, both in Germany and Italy, embossed decoration began to be employed on parade armor. In Germany, this arose as a continuation of a late medieval tradition of mummery and fanciful court pageantry; in Italy, it was a more conscious revival of antique Roman imagery, particularly in the hands of the famous Negroli armorers of Milan and their contemporaries, who also inspired the employment of this technique in France and the Low Countries.

Another vogue that appeared about the same time— no doub inspired by the continuous contact, belligerent or otherwise, between Europe and the Ottoman empire —was a taste for everything deemed “Oriental.” The fashion influenced court life, and elaborate “Turkish tournaments” were held at the Habsburg court , in which the participants were dressed in the Ottoman style, wearing turbans or pointed helmets, long kaftans, and carrying sabers and shields. Some of the arms and armor were undoubtedly originally acquired by booty, gifts, or as trade items from the Turks.

Soon, however, copies were being made in Europe that closely mirrored Ottoman style in construction, shape, and decoration, although horse armor was rarely affected by this fashion.

Military tactics and weaponry changed dramatically during the sixteenth century, as infantry grew in importance and handheld firearms (even for the mounted man-at-arms) became the weapons of choice. The fully armored warrior on a barded horse became an increasingly rare sight on the battlefield. After the 1580s, the man’s armor was gradually reduced to three-quarter length (omitting defenses for the lower leg and foot), but was sometimes supplemented with shot-proof reinforcing plates. Similarly, the full bard was abandoned in favor of a shaffron and saddle steels, if indeed any horse armor was worn at all.

By the end of the sixteenth century, full bards were an anachronism for all but ceremonial occasions. Few were being made, usually for members of royal families, and the small number of surviving examples were clearly intended to impress. Possibly the latest such garniture is the one constructed for Louis XIII of France about 1630–40, which includes a full bard with shaffron and crinet of contemporary French manufacture, while the peytral and crupper are constructed of much older elements dating to about 1500–1510, decorated to match. These earlier elements were no doubt commandeered from an arsenal, saving the armorer valuable time. To contemporaries who saw the sovereign dressed in armor astride a fully barded horse, the sight must have been a nostalgic evocation of an age that had long since passed.

Postscript

Horses remained an essential part of armed conflict in most parts of the world until the early twentieth century. But while many soldiers—especially those of specialized units—continued to wear some elements of armor until the early nineteenth century, and then again since World War I, horses were no longer protected with armor. Among the few notable exceptions are leather coverings used in North America to protect horses against Indian arrows, or the similar heavy leather panels still used today in the bullfighting arenas of Spain and Mexico. Last but not least, mention should be made of the great Sudanic African empires, where quilted horse armor remained in active use until the twentieth century; and in parts of Niger and Sudan, these armored horses continue to take part in traditional ceremonies to the present day.